Villiers Engineering LTD. Wolverhampton

The History of Villiers Engineering Ltd.

Villiers came into being in 1898 because John Marston was a little man.

John Marston was a Wolverhampton tinsmith: 1898 was the time that the bicycle as we know it today was becoming the vogue.

But there was no choice of frame size in those days and John Marston’s short legs could not reach the pedals in comfort. The bicycle, it appeared, was not for him.

As always, however, the need produced the man – William Newill, a foreman in John Marston’s factory, who saw an opportunity of doing ‘the boss’ a good turn. “Let me make you a bicycle, sir,” he suggested. The thought of possessing a ‘tailor-made’ bicycle appeal to John Marston in more ways that one and William Newill was given the ‘go ahead’.

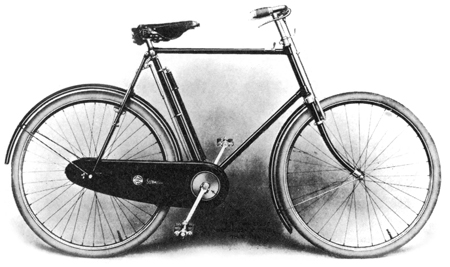

Newill belonged to an era of craftsmen – an era in which men were dominated by pride in a job well done – and there can be little doubt that the bicycle he made for John Marston was superior to any other machine on the road. Its gleaming black finish with gold lining made it a thing of beauty. It was christened the ‘Sunbeam Cob’.

Later, because it collected a lot of dirt, the chain was completely enclosed, and it was in this form that the machine became the prototype of the Sunbeam – probably the most famous bicycle in the world. The chain case, of course, became known as the ‘little oil bath’, with which every Sunbeam bicycle was subsequently fitted.

John Marston and his son Norman en route to work.

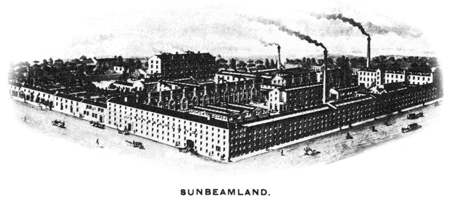

Sunbeamland

Mr Marston was so impressed by the machine that he disposed of his tinplate business in order to produce Sunbeam bicycles. Pedal production, however, proved something of a problem and John Marston sent his son, Charles, to America to study manufacturing methods.

Charles brought back American machinery for which there was no room at the Sunbeam factory and John Marston overcame the problem by buying a tiny factory in Villiers Street, Wolverhampton, and founding a company whose sole function was to make pedals for Sunbeam Bicycles.

The company was registered in 1898 as The Villiers Cycle Component Company, with Charles Marston as the Managing Director and with a labour force of eight men. Thus Villiers was born.

In a very short time pedal production outstripped the Sunbeam requirements and the surplus was made available to other bicycle manufacturers. This, perhaps was the most far-reaching event in the history of Villiers for it bought into their sphere of operations Frank H. Farrer, the man who saw into the future and laid the foundations which the now powerful organisation is built.

In 1902 Villiers began making bicycle freewheels and these became so much in demand that pedal production ceased a year or so later to enable everything to be concentrated on freewheels.

Villiers ultimately became the world’s biggest producers of freewheels, the output of the Wolverhampton factory during the peak years after the second world war exceeding 80,000 per week – more than four million a year! Exporting to most countries of the world Villiers remain the world’s most prolific producer of bicycle freewheels.

The real turning point in Villiers’ career, however came in 1912, when Frank Farrer persuaded Charles Marston that there was a market for a proprietor motor-cycle engine. The following year the first Villiers engine appear.

It was a four-stroke of 350 c.c capacity with an integral two-speed gearbox, a friction clutch, an overhead inlet valve and a side exhaust valve. A motor cycle fitted with one of these engines lapped Brooklands at 46 miles an hour – no mean performance.

But the engine was condemned by the British motor cycle manufacturers as being ‘too advanced’ and it never went into serious production.

Fortunately for Villiers, Frank Farrer was not a man to be denied. He had recently been made director of Villiers – by this time renamed The Villiers Engineering Co. Ltd. – and he was determined that his company should make motor-cycle engines.

Accordingly, he turned his attention to a two-stroke unit, a type of engine with a rather poor reputation at that time. Frank Farrer, however, convinced himself that a two-stroke engine would give the required reliability and performance if it was built to the same standards of quality and workmanship for which Villiers had already become renowned.

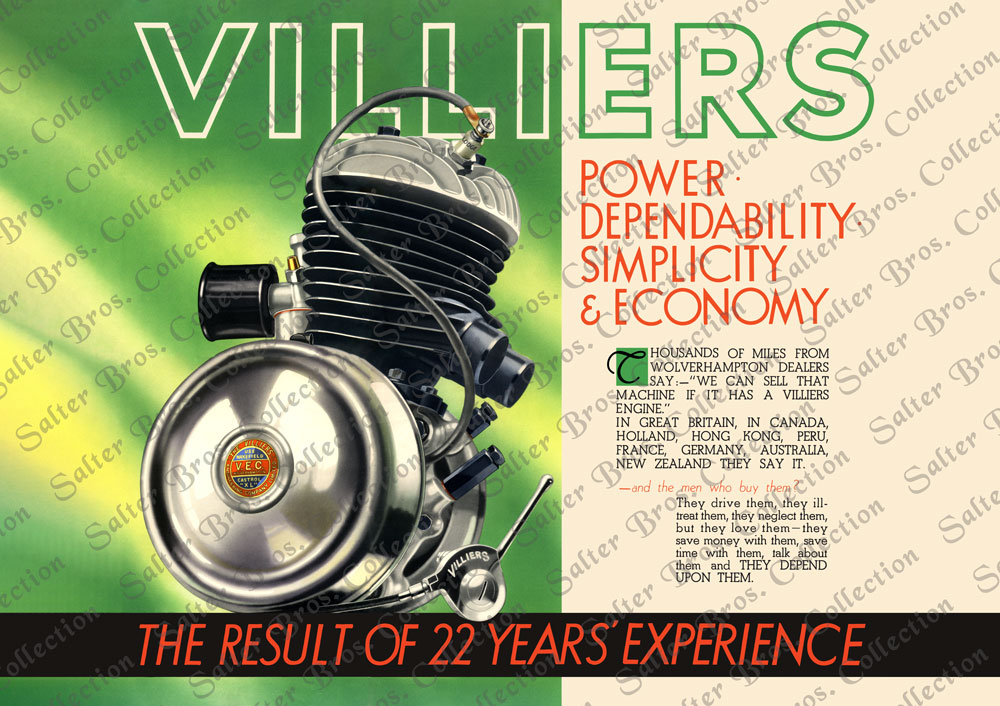

A beautiful Villiers Engine poster which is available for purchase from our online store – click here.

A two-stroke engine was design and built and fitted into a specially constructed frame. Mr Farrer, himself tested the machine on the Birmingham-Bridgnorth road, and so enthusiastic was he about its performance even on this initial run that he told Mr Marston that he could “Sell thousands of them”. Since then more than two and a half million Villiers engines have been sold! (Up until 1959).

Engine production began in 1913 and was checked by World War I, but even this proved something of a blessing in disguise for, with the supplies of German magnetos cut off, Villiers designed their now famous flywheel magneto.

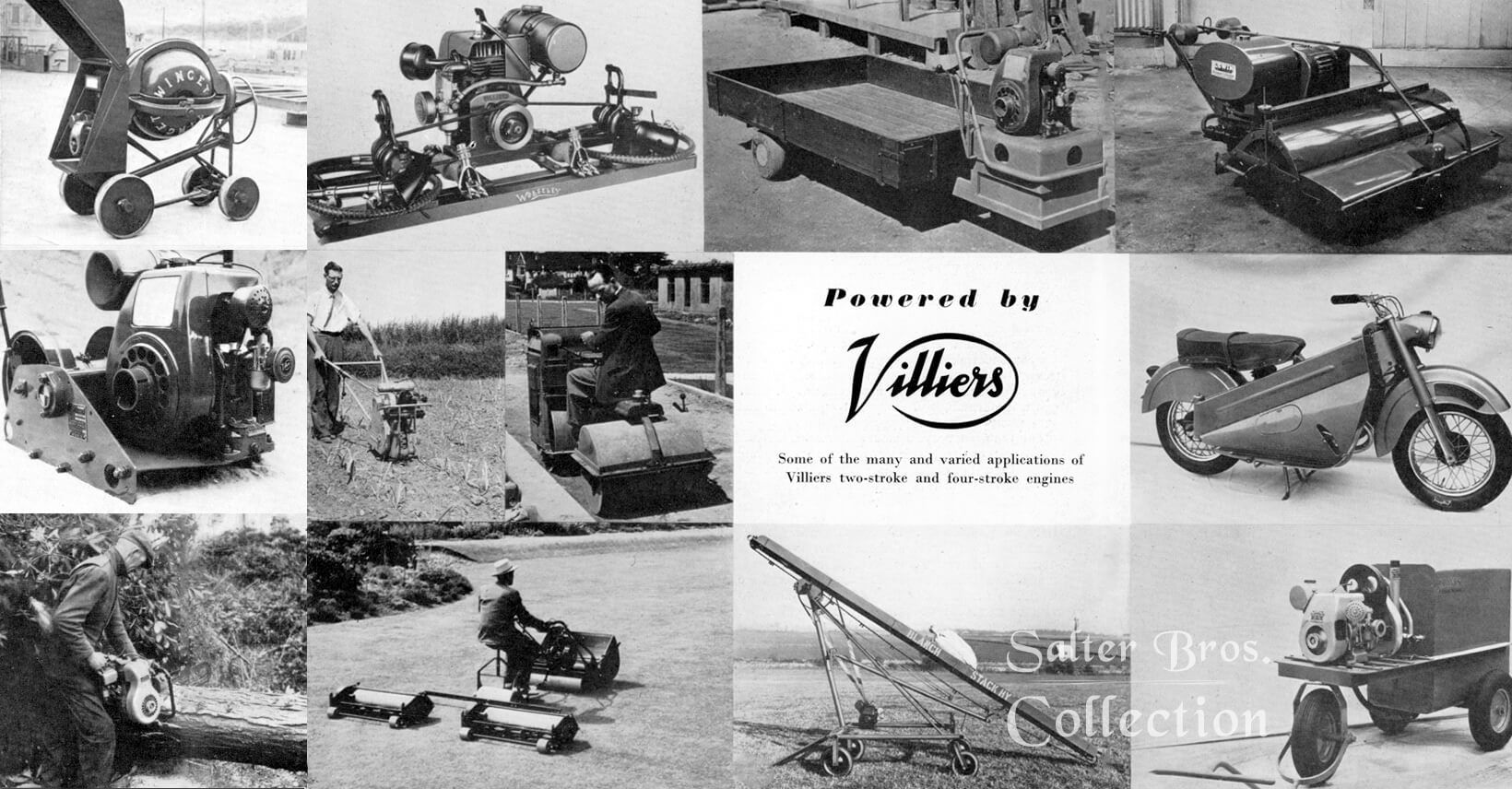

With the war over engine production was soon in full swing and in 1919 a 269 c.c unit was adapted to drive a lawn mower – a successful venture, which led to the design and production of a range of two-stroke engines for agricultural and industrial applications.

For many years Villiers concentrated solely upon two-stroke engines, but the Second World War proved yet another important turning point in their progress, the British Government requesting a small-capacity four-stroke engine to drive pumps and generator sets for the Armed Forces and Civil Defense Services.

The success of that unit heralded the introduction of the wide range of Villiers four-stroke engines, which like the two-strokes, now have a tremendous variety of applications in agricultural, horticultural and industrial spheres.

The new 1959 Villiers D-270 Diesel Engine.

This colourful poster is available from our online store.

Click Here.

Since engine production began in 1912, the Villiers story has been one on constant expansion, and behind many of the moves the shrewdness and foresight of Frank Farrer was apparent.

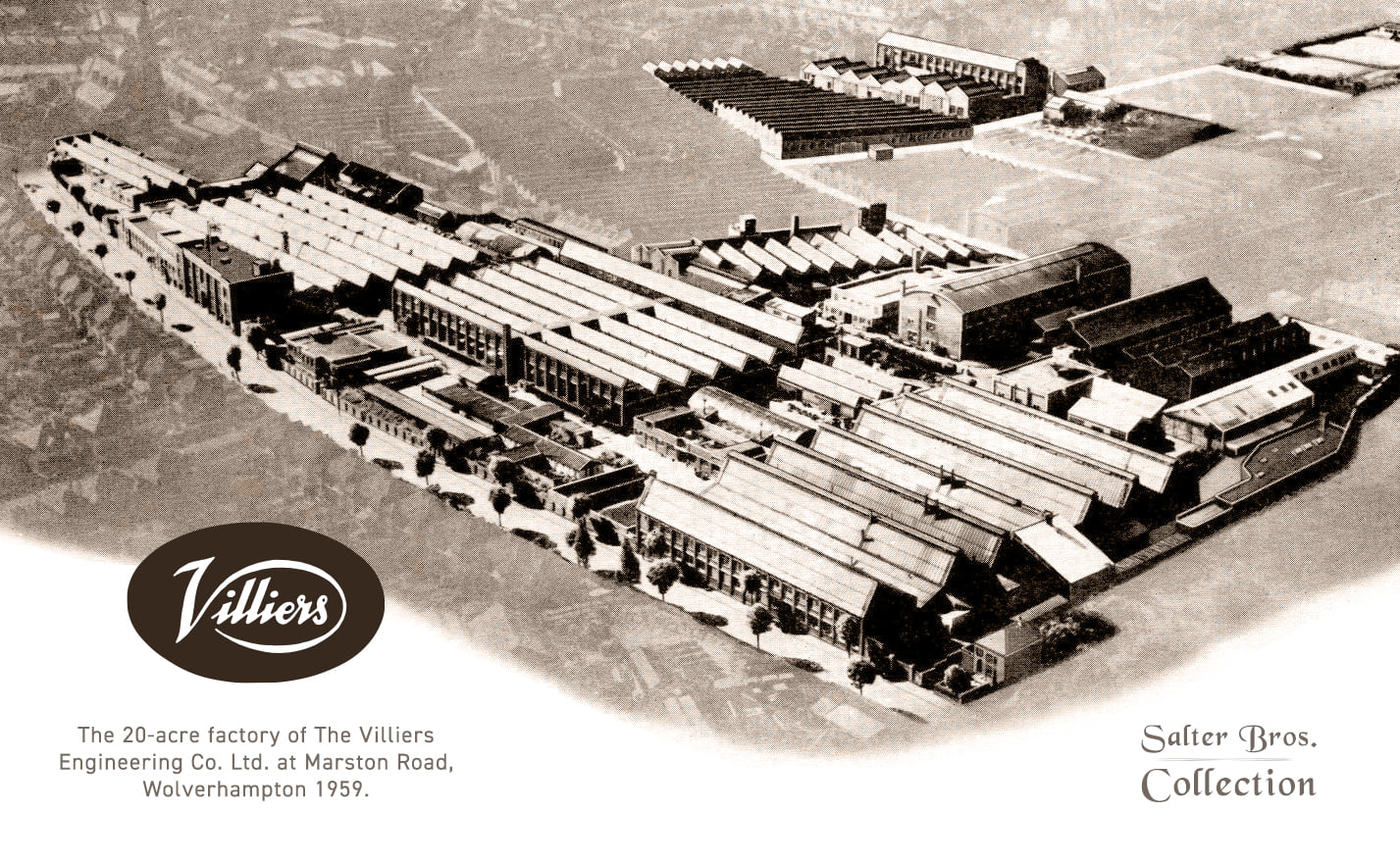

Villiers started life in a tiny factory converted from three terrace houses covering approximately on-eighth of an acre. today in 1959 the impressive Villiers plant at Wolverhampton overlooks the original factory and covers approximately 20 acres and employs nearly 2,000 people.

Growth in output is particularly interesting.

By 1939 two weeks’ production equaled the annual figure of the early 1920s: in 1955 the daily production exceeded the weekly figure of 1939. in 45 years Villiers have produced more than two and a half million engines – and to give some idea of the tremendous post-war development nearly two million have been built since the end of the second world war.

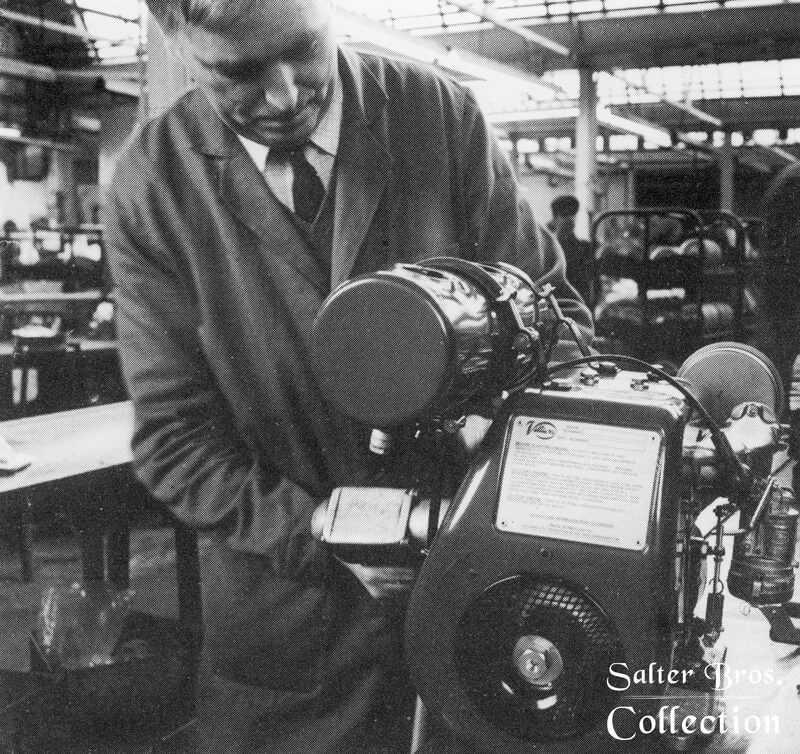

But Villiers have not merely grown. Expansion has always followed a pattern devised in the earliest days by Charles Marston and Frank Farrer – a pattern which led ultimately to as complete self-sufficiency as was possible. Villiers and quality had always gone hand-in-hand from the days the first bicycle freewheel was forged and the architects of the Villiers empire decided that the desired standards of quality could only be attained and maintained by themselves controlling the production of all components from raw materials to the finished product.

Consequently foundries, laboratories, drop forges, heat treatment and plating shops and test and experimental sections have all been installed to make the Villiers factory one of the most self-sufficient of its kind.

Today (1959), practically every component part of the extensive range of standard engines, with the obvious exception of such items as spark plugs, control cables and pedal rubbers, is of Villiers design and manufacture. Villiers manufacture their own magnetos, carburettors, gearboxes and silencers – and over the production of every item is exercised an inflexible control of quality of materials and workmanship. And this quality control begins with raw materials enter the factory, no metals being released for production until they have passed stringent laboratory tests.

Having built their reputation on the quality and dependability of their products Villiers spare no effort in preserving it, for on the reliability of their engines depends very largely the reputation of manufacturers in all parts of the world who use them to power their products. In recent years Villiers have implemented an immense expansion policy – a policy which culminated in 1957 in the acquisition of J. A. Prestwich Industries Limited, manufacturers of the famous JAP engines.

This brought together two of the world’s oldest and best-known small engine manufacturers and saw also the biggest step to date in the development of the Villiers Group of Companies. The merger involved Pencils Ltd., one of Britain’s most prolific pencil manufacturers, with an output of forty million yearly, and, in Australia, J. A. Preswich-Virtue Pty. Ltd., bringing the number of companies under Villiers control to seven.

Before this, the expansion policy saw the creation in 1953 of Villiers Australia Pty. Ltd., at Ballaarat, Victoria, where already thousands of Villiers engines are being built every week to feed the growing demand for powered machinery in Australia.

In 1956 Villiers acquired the Wednesfield steel pressing firm of Robert Harris Ltd., and the following year, also at Wednesfield, a factory was built to house the newly created company of Villiers (Tool Developments) Ltd., who have already established a reputation as producers of special purpose precision tools, not only for the Villiers Group but for some of the biggest names in the British aircraft and motor industries.

Villiers Group products are renowned throughout the world and their current export activities can be gauged from the direct trading accounts with approximately 140 different overseas countries. The engines have performed without detriment to their established reputation for dependability in some of the most adverse conditions. They have operated in the frozen wastes of Greenland and Norther Scandinavia and in the steamy heats of the tropics.

They powered rock drills, air compressors and lighting sets during the building of the world’s highest road across the Andes mountains. They are used for quarrying; they have powered light aircraft; and also stretches of Scandinavian coastline Villiers engines stand by to drive emergency generating sets should a mains electricity failure put the lighthouses out of commission. Villiers, too, is the backbone of the British two-stroke motor cycle industry and their range of specially designed engines was primarily responsible for the creation of an all-British scooter industry.

Speedway racing throughout the world virtually owes its existence to the 500 c.c. JAP speedway engine. In spanning the last sixty years (1898 – 1958) Villiers and JAP have accumulated knowledge and experience without equal in the sphere of small engines. The future is full of new challenges. Villiers will meet them as they have met them in the past – with justifiable confidence in the performance and dependability of their engines.

Villiers Group engines will continue to be ‘The Heart and Power of the Finest Machines’.

A Beautiful hand sketch by Hanslip Fletcher 1944.

Villiers Engineering, Wolverhampton Factory, UK

The video that you are about to view is something extremely rare and special in our Villiers Engine and ephemera collection.

These are all original photos of the Villiers Wolverhampton factory.

The photos were taking in the 1940s and represents all the major areas of the factory. The video covers engine production from the laboratory right through to casting, machining etc. and bicycle free wheel hubs department.

I hope you enjoy the video as much as I enjoyed making it.

Click on the video above to watch it.

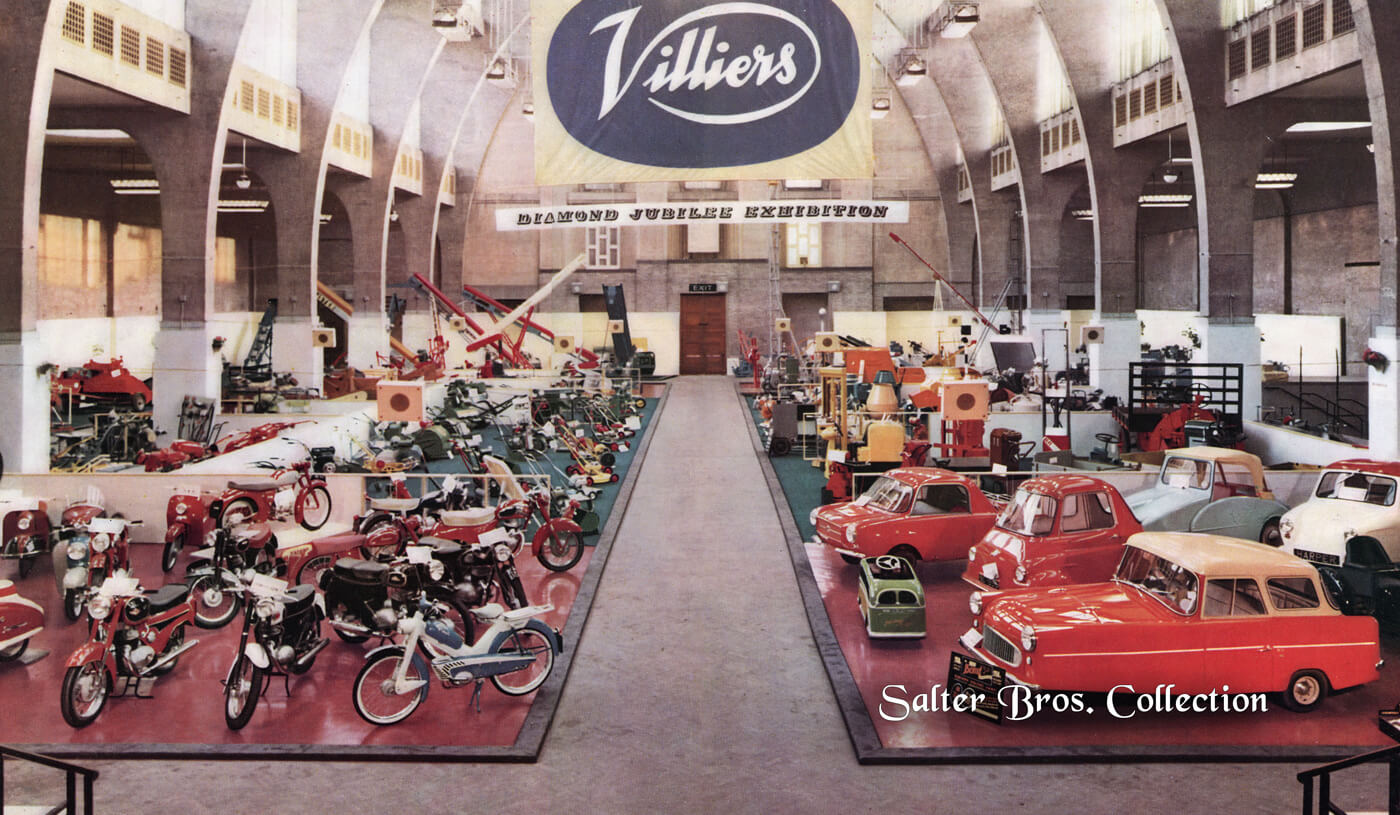

Villiers Diamond Jubilee Exhibition – 1959

A range of Villiers powered equipment below, ranging from cars, motor bikes, scooters and farm machinery.

The Villiers Group of Companies (1959)

Hon. President: Frank H. Farrer

Directors: Leslie W. Farrer and H. Geoffrey Jones (Joint Managing)

George T. Teasdale and T. P. Walmsley.

Head Office: Marston Road, Wolverhampton

London Showroom: 190 Piccadilly, W.1.

The Villiers Engineering Co. Ltd.

Marston Road, Wolverhampton, Staffs.

Villiers Australia Pty. Ltd.

Ballarat Victoria, Australia

J. A. Prestwich Industries Ltd.

Northumberland Park, Tittenham, London, N. 17

Chelmsford Road, Southgate, London, N.14

Robert Harris Ltd.

Waddens Brook, Wednesfield, Staffs.

Villiers (Tool Developments) Ltd.

Waddens Brook, Wednesfield, Staffs.

Pencils Ltd.

Northumberland Park, Tottenham, London, N.17

J. A. Prestwich-Virtue Ptd. Ltd.

Rosebery, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Associate Company:

Hispano Villiers S.A.

San Andres, Barcelona, Spain.

Manganese Bronze Holdings PLC.

The Chairman of Manganese Bronze Holdings PLC was Dennis Poore.

Manganese Bronze Holdings was an engineering company who’s primary product was making marine propellers.

Dennis Poore decided that he was going to sell off the propeller part of the business to give him a little more funds to buy up failing British motorcycle companies.

He purchased: Associated Motor Cycles, Norton, AJS, James, Francis-Barnett, Matchless and Villiers Engineering.

After BSA collapsed in 1972, he completed a deal with the UK Government and liquidators to buy BSA/Triumph and merged them together with his other brands to form Norton Villiers Triumph Ltd. Dennis Poore became the chairman of Norton Villiers Triumph and shortly after sold off BSA’s non motorcycle sides of the company.

Dennis went on to restructure the company to make it more compedative and to turn a profit. This led to making 3,000 of the company’s 4,500 employees redundant.

In 1972 when Manganese Bronze Holdings purchased BSA, the subsidiary company of Carbodies came with it.

They were the buildings of the FX4 London Taxi. Carbodies was previously known as London Taxis International &The London Taxi Company.

Manganese Bronze Holdings Now owns Villiers Engineering

The Guardian – 21 April 1965

Manganese Bronze Holdings now owns Villiers Engineering. Acceptance of the recent offer have increased the Manganese holding of Villiers ordinary shares to 91 ½ per cent and the preference shares to 96 per cent.

Villiers buys AMC’s Motorcycle side

The Guardian – 14 September 1966.

The motor-cycle side of the Associated Motor Cycles, the company whose quotation was suspended by the Stock Exchange following its financial difficulties has been sold to Villiers Engineering, the Wolverhampton subsidiary of Manganese Bronze Holdings, by the receiver and manager. This deal will ensure the continuance of the manufacture and distribution and export of Associated’s machines which includes the Norton, Matchless, AJS, and James range.

Although the company has been in great difficulties, there has been a growing demand for the machines, especially from America. Recently, Mr Joseph Berliner, president of Berliner Motor Corporation, offered to take all the machines that the company could produce.

At one stage he said he was prepared to put in up to £500,000 of his company’s money to ensure continued production of the motor cycles.

The news for shareholders, however, is much bleaker, in spite of the sale, since it has been stated that the financial position of the company is such as to make it extremely unlikely that there will be a payout to shareholders. The price paid for the motor cycle side of the firm was not announced, but it is understand that Villiers, which manufactures small internal combustion engines has bought the business and in addition, leasehold rights over the property.

Villiers goes into liquidation

1975

Villiers, a part of the Norton Villiers Triumph Motorcycle group goes into liquidation.

Putting the spark back into Villiers

Britishbusiness – 3 December 1981

There is no shortage of sceptics willing to write off any company bought from the liquidator, but in a former motorcycle factory in Wolverhampton, David Sankey, managing director of Villiers, is proving the Jonahs wrong by making industrial engines for a growing export market.

If you can remember when Britain had a meaningful motorcycle industry, you may recall that many of the smaller bikes were powered by a two-stroke Villiers engine. About the same time many lawnmowers were also Villiers powered.

Things might still be the same now if it were not for two invasions — one from Japan, the other from the United States.

The Japanese motorcycle invasion wiped out most of Britain’s motorbike industry and took away a large proportion of Villiers’ customers. From the United States, Briggs and Stratton began undercutting Villiers engine prices for grass cutting machinery, removing another large section.

The crunch came in 1975 when Villiers, part of the Norton motorcycle group, went into liquidation. But as is so often the case, this is not the end of the story.

The following year David Sankey and his colleague, financial specialist Mark Scutt, bought the Villiers engines part of the business from the receiver, with financial assistance from the Department of Industry. The deal bought

them half the original Norton Villiers factory on 52 acres of ground in Wolverhampton and about 500 machine tools including those needed to manufacture Villiers engines.

The deal was complicated. For instance, because the former marketing company was still in existence selling spare parts — and calling itself Villiers Engines Ltd — the new company had to call itself Wolverhampton Industrial Engines, although it was allowed to use the Villiers trade mark.

It was not able to call itself Villiers Ltd until March 1980. Managing director David Sankey recalls the doubts when the company was re-started. `Because the company had not been producing anything for about a year, there was considerable scepticism as to whether we would get it going at all,’ he says.

But, if there is such a thing, the old Villiers company had been liquidated at a convenient time. ‘It was a fortunate time to go bankrupt,’ according to Mr Sankey. ‘The marketing company had a large number of engines in stock at the time of liquidation, and although there was a shortage, it wasn’t dramatic, and the effect was not too disastrous.’

But if the customers had scarcely noticed the demise and rebirth of Villiers, the suppliers to the old Villiers company certainly had.

Like many engine makers the former company had bought in many of its specialised components such as pistons, valves and bearings.

`A lot of suppliers had lost money on the liquidation and we had a few who tried to make up the money they had lost by overcharging us,’ said Mr Sankey. But for the most part the

suppliers were cooperative and re-started deliveries on the basis that it was better to get some business back rather than get nothing. After the loss of its motorcycle and lawnmower business, Villiers’ main strength was in the manufacture of good-quality reliable industrial engines — single-cylinder, four-stroke units which powered concrete mixers, pumps, generators and the like.

Production of these engines restarted in 1977 with an unexpectedly well-filled order book. It seems the old company was habitually late with deliveries. ‘A lot of overseas customers had got so used to Villiers being late that they hadn’t even noticed that the company had gone into liquidation, so we had quite a lot of outstanding overseas orders,’ said Mr Sankey. The new company ended 1977 with a small profit.

The 500 machine tools that the new company had inherited from Norton Villiers were considerably more than were needed to make small engines, but the surplus had its advantages.

Out of today’s workforce of 170, about 100 are employed in the machine shop, so there are in effect five machines per man.

Although this is highly inefficient on machine utilisation, the surfeit of machine tools saves on setting time — as one machine can be used for just one job — and the low utilisation means fewer breakdowns.

Although the system means there are very few wasted man-hours, David Sankey admits the arrangements can’t go on for ever because many of the machines date from the 1950s and 1960s, but he points out that it works well when re-starting a business providing the machines haven’t cost a lot.

Using this system, output in 1978 rose to 600 engines a week, but not without working a lot of overtime, and the new company began to look for ways of improving its efficiency, with measures ranging from the use of new materials so engine components could be made more cheaply to the purchase of more up-to-date machine tools from the growing number of factory auctions.

One of the company’s latest purchases is an automatic multi-station transfer machine which in 1977 cost £185,000.

It was picked up at the Prestcold auction in Paisley for around £100.

The improvements in efficiency were severely tested in 1979 when the Iranian revolution took away a market which had bought 5000 engines the previous year.

Greater efforts selling into the home market meant the company ended the year with a small loss.

But out of the gloom of 1979 came a new idea.

In a nutshell it was this: instead of selling bare engines to — say — a pump manufacturer who then sells the complete unit, why not buy in the pump and sell the unit as a complete Villiers package? The move seemed an appropriate one because many makers of pumps, generators and other engine-driven equipment, faced with declining orders, had been abandoning Villiers for cheaper engines in an effort to reduce their prices.

As David Sankey put it: ‘What we are doing is saving ourselves before they go.’ He points out that two-thirds of the value of a pumping set is accounted for by the engine. ‘It is absurd that the person who is producing one-third of the value is buying two-thirds of it to put together,’ he says. ‘It is better that we should buy the pump, do the marketing and sell the thing ourselves.’ With a developed overseas sales network, Villiers is already selling a pressure-washing set which has drawn large orders from Nigeria.

Selling a complete unit involves Villiers in carrying spares for the equipment that is driven by its engine, but on the credit side, working this way means the company can choose equipment which has a reputation for efficiency and reliability.

One of the selling points of Villiers industrial engines has always been their simplicity and ease of overhaul. Over the years, as components have been improved, they have been made interchangeable with earlier components which makes the supply of spare parts comparatively simple. As major modifications such as the proposed change to transistorised ignition are made, the policy of interchangeability may not always be possible.

But no change is made unless it brings about significant cost reduction while at the same time maintaining or improving on quality. Since the new owners took over, the efficiency of existing engines has been improved and today’s engines consume around 50 per cent less oil and between 15 and 20 per cent less fuel than the engines produced before liquidation.

Although Villiers has no plans to take on Briggs and Stratton making cheap engines for the mass-produced lawnmower market, it has picked up some lawnmower business since the new company was formed. Ransomes Sims and Jefferies, which supplies most ‘professional’ mowers for local authorities will offer Villiers engines as orig-inal equipment as an option to the Briggs and Stratton unit next year.

The old Villiers company once provided engines for Ransomes mowers, but this arrangement was terminated in 1974.

In a way the new company can thank local authority groundsmen and greenkeepers throughout Britain for the Ransomes deal.

Many a parks department manager, familiar with a Villiers-powered machine, has been ordering a Villiers replacement engine for the council’s Ransomes mower when the Briggs and Stratton one wore out, and Villiers has been supplying the unit as a bolt-on replacement, tailored to fit the B&S mountings.

Some councils even ordered their mower without an engine and bought the engine separately from Villiers. Now their favourite mower with their favourite engine will be available from one source. The future? David Sankey confidently says that nobody makes a better engine for the purpose than Villiers, but he’s well aware that the company is not yet big enough to tackle the likes of Briggs and Stratton, Renault, Honda, Fuji-Robin and Mitsubishi head-on.

But at the moment the company is working flat-out producing 650 engines a week, with the vast majority of them for export to such places as Nigeria, Iran, Pakistan, east Africa, Portugal and Hong Kong.

He confesses he hasn’t got round to studying the European market closely yet, but sees opportunities in Scandinavia and the Benelux countries, despite opposition from French, Swiss and Italian competitors. ‘After all if the Japanese have some success there — so can we,’ he says.

1988 Villiers Staff Photo

In 2021 I was lucky enough to buy this old staff photo off EBay.

For those wondering if 1988 is a typo, no it isn’t, Villiers was still manufacturing engines in Wolverhampton under the directorship of David Sankey and Mark Scutt.